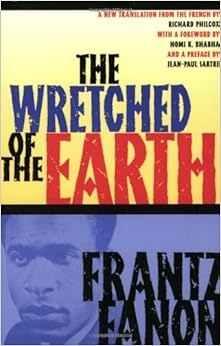

Reading Frantz Fanon’s The Wretched of the Earth (1961 – translated by Richard Philcox) has

been a troubling event for me. I have only recently become aware of his work,

and this is the first of his writings that I’ve read. And these are some of my

initial reactions to this influential writing.

I am immediately divided in my opinion. On the one hand I am impressed by his vigor and fire, his energy. His passion–and I use that word with its emphasis on pain–from the Latin “to suffer.” His analysis of the colonized peoples struggle against the power of the colonizers is infused with anguish and anger. And rightly so. Fanon wrote as an intellectual, yes, but not as an ivory tower elite. His words are not dull academic discussion of distant problems, but cutting; they bleed. They scream.

Fanon was not only (and maybe not primarily) a revolutionary, but also a psychiatrist. I am prepared to accept his analysis of the psychological motivations of colonized people (not just in the historical context of his writing – during the Algerian Revolutionary War- but today as well, in the context of people of color in the United States).

But I am, on the other hand, deeply distressed by his (apparent) emphasis on the necessity of violence. When he writes “At the individual level, violence is a cleansing force… (Fanon, 51)” the pacifist in me objects, and loudly. In fact, Fanon is frequently criticized for his prescription for redemptive violence.

I am immediately divided in my opinion. On the one hand I am impressed by his vigor and fire, his energy. His passion–and I use that word with its emphasis on pain–from the Latin “to suffer.” His analysis of the colonized peoples struggle against the power of the colonizers is infused with anguish and anger. And rightly so. Fanon wrote as an intellectual, yes, but not as an ivory tower elite. His words are not dull academic discussion of distant problems, but cutting; they bleed. They scream.

Fanon was not only (and maybe not primarily) a revolutionary, but also a psychiatrist. I am prepared to accept his analysis of the psychological motivations of colonized people (not just in the historical context of his writing – during the Algerian Revolutionary War- but today as well, in the context of people of color in the United States).

But I am, on the other hand, deeply distressed by his (apparent) emphasis on the necessity of violence. When he writes “At the individual level, violence is a cleansing force… (Fanon, 51)” the pacifist in me objects, and loudly. In fact, Fanon is frequently criticized for his prescription for redemptive violence.

Walter Wink coined the phrase “redemptive violence,”

noting that the idea goes back to the creation stories of ancient Babylon

wherein the world was created in catastrophic acts of violence-and that the idea

continues to influence the modern world. We fight revolutions, invade countries,

and topple governments with military force because we believe that we can

create something better from the ashes.

I will make a few observations about The Wretched of the Earth that may, or

may not ameliorate those concerns (though I concede that I am not a Fanon scholar

and do write authoritatively…)

1) Fanon used brusque declarative statements describing

what was happening and what he projected would happen the future. “The underprivileged

and starving peasant is the exploited who very soon discovers that only

violence pays…Colonialism is not a machine capable of thinking… it is naked

violence and only gives in when confronted with greater violence. (Fanon, 23)”

And it is very easy to read this type of sentence as prescriptive instead of merely

descriptive. To say that something “is” is not necessarily the same as saying

that something “should be.”

2) The first chapter “On Violence” really needs to be read along with the final chapter, “Colonial War and Mental Disorders” wherein Fanon describes the debilitating psychological effects of violence on both the perpetrator and the victim. If you stop reading and toss the book aside after the first chapter you’ll have missed an important part of the book. IF Fanon is prescribing violence as the means to effecting revolutionary change, he is not doing so unconditionally.

2) The first chapter “On Violence” really needs to be read along with the final chapter, “Colonial War and Mental Disorders” wherein Fanon describes the debilitating psychological effects of violence on both the perpetrator and the victim. If you stop reading and toss the book aside after the first chapter you’ll have missed an important part of the book. IF Fanon is prescribing violence as the means to effecting revolutionary change, he is not doing so unconditionally.

3) Some of the more powerful pro-redemptive

violence statements are actually found in Jean-Paul Sartre’s preface rather

than in Fanon’s work. Sartre wrote “Violence…is

man recreating himself, (Sartre, lv)” and “Will we recover? Yes. Violence, like

Achilles’spear, can heal the wounds it has inflicted (lxii).”

4) This particular edition of The Wretched of the Earth is prefaced with a forward by Homi K. Bhabha–an important figure in post-colonial studies. Bhabha says that “It is difficult to do justice to Fanon’s views on violence,” noting that, while Fanon described the doctrine of liberatory violence, Fanon the man, deep down hated it. (Bhabha, xxi)

The Wretched

of the Earth is a powerful work, passionate and angry. But it is a clouded

book. Perhaps a fire with more smoke than heat and light at times. That said, I am not

through with Fanon. I will continue to think about this one, and seek out his

other works as well.

Fanon, Frantz, Richard Philcox, and Homi K.

Bhabha. The Wretched of the Earth. New York: Grove, 2004.

No comments:

Post a Comment