The Grapes of Wrath – Movie Night Discussion Guide

In the mid to late

1930s a series of Dustbowls – dust storms that darkened the skies across nearly

the entire nation – devastated the Great Plains of the United States and

Canada. Powerful winds, picking up dirt

and dust from the ground made the sky appear black all the way to Chicago. Eventually the soil was completely lost as it

was blown out to the Atlantic Ocean.

Topsoil across millions of acres was blown away because of the indigenous

sod had been broken for wheat farming and the vast herds of bison that once

fertilized that sod were gone, nearly exterminated.

With their crops ruined, lands barren and dry, and homes foreclosed for unpayable debts, many farm families gave up and left. They left homes and farms that had been part of their families for generations to look for a better life elsewhere. Many of the displaced were from the state of Oklahoma, where 15% of the state’s population left. The migrants were often called Okies whether they were from Oklahoma or not.

This is the setting of John Steinbeck’s powerful novel, and the equally gripping 1940 movie version directed by John Ford, the mass migration of people for the “Promised Land” of California and the promise of good jobs with decent pay. But that promise would remain unfulfilled. In California the Okies found, not the sweet nectar of grapes running down their chins, but the “Grapes of Wrath.”

With their crops ruined, lands barren and dry, and homes foreclosed for unpayable debts, many farm families gave up and left. They left homes and farms that had been part of their families for generations to look for a better life elsewhere. Many of the displaced were from the state of Oklahoma, where 15% of the state’s population left. The migrants were often called Okies whether they were from Oklahoma or not.

This is the setting of John Steinbeck’s powerful novel, and the equally gripping 1940 movie version directed by John Ford, the mass migration of people for the “Promised Land” of California and the promise of good jobs with decent pay. But that promise would remain unfulfilled. In California the Okies found, not the sweet nectar of grapes running down their chins, but the “Grapes of Wrath.”

In 1937 California passed the so-called “Anti-Okie Law” which stated: Every person, firm, or corporation, or officer or agent thereof that brings or assists in bringing into the State any indigent person who is not a resident of the State, knowing him to be an indigent person, is guilty of a misdemeanor.” The statute was eventually overturned in 1941.

The title of the novel

and subsequent film – suggested to Steinbeck by his first wife – was drawn from

“The Battle Hymn of the Republic” He is

trampling out the vintage where the grapes of wrath are stored… Steinbeck said that when he wrote The Grapes of Wrath he was “filled…with

certain angers… at people who were doing injustices to other people.” The writing of the book was his response to

the injustice he saw committed against the poor and helpless.

Proverbs: 14: 31 – If you oppress poor people, you insult the God who made them, but kindness shown to the poor is an act of worship.

Proverbs 21: 13 – If you refuse to listen to the cry of the poor, your own cry for help will not be heard.

Proverbs 22:9 – Be generous and share your food with the poor. You will be blessed for it.

… if a fella’s got sompin to eat an’ another fella’s hungry – why the first fella aint got no choice. (Grapes, 66)

The movie ends on a

much more positive note than the novel – with Ma’s declaration that she won’t be

scared any longer, and that “we’ll go on

forever, Pa, because we’re the people.” The

family is safe – at least temporarily – in the government camp and in the

promise of “twenty days work.” The novel, however, is not quite that

upbeat. It’s not hopeless, but the hope is a deeply troubled hope, a hope that has

hurt, continues to hurt, but goes on despite.

Their hope is built in community, in unity with “our own people,” people working together.

The shocking conclusion of the book – omitted from the movie – was considered scandalous and prurient by many, and led to the book being banned from many libraries. Rose of Sharon’s baby is stillborn, the family is forced to move out of the security of the camp, and Tom has left the family. But they continue, doggedly struggling to work and to live. The Joads, who don’t have much themselves, continue to share what little they have, Rose of Sharon going so far as to feed a starving old man her own breast milk.

Steinbeck wrote, “I am not trying to write a satisfying story. I have done my damndest to rip a reader’s nerves to rags. I don’t want him satisfied.” Indeed, the book left many people unsatisfied. They reacted with a fierce hostility to the book, calling it “a lie, a black infernal creation of the Marxist, Soviet propaganda.” Ministers, republicans, bankers, senators and librarians denounced it as communist, immoral, degrading, warped and untruthful.

It’s a powerful work of anger, but not a hateful, destructive anger. Steinbeck’s anger, and Ford’s, was directed against injustice and oppression. In this way, their anger is a motivating energy, driving us to learn from each other, and to stand with each other to create a better world for the whole community.

The shocking conclusion of the book – omitted from the movie – was considered scandalous and prurient by many, and led to the book being banned from many libraries. Rose of Sharon’s baby is stillborn, the family is forced to move out of the security of the camp, and Tom has left the family. But they continue, doggedly struggling to work and to live. The Joads, who don’t have much themselves, continue to share what little they have, Rose of Sharon going so far as to feed a starving old man her own breast milk.

Steinbeck wrote, “I am not trying to write a satisfying story. I have done my damndest to rip a reader’s nerves to rags. I don’t want him satisfied.” Indeed, the book left many people unsatisfied. They reacted with a fierce hostility to the book, calling it “a lie, a black infernal creation of the Marxist, Soviet propaganda.” Ministers, republicans, bankers, senators and librarians denounced it as communist, immoral, degrading, warped and untruthful.

It’s a powerful work of anger, but not a hateful, destructive anger. Steinbeck’s anger, and Ford’s, was directed against injustice and oppression. In this way, their anger is a motivating energy, driving us to learn from each other, and to stand with each other to create a better world for the whole community.

Questions and Reflections

What is more important – ownership and possession or work and labor?

How does Jim Casey, the former preacher, embody a “Christ figure”?

“They payin’ you 5¢?” “Come now, you rich people, weep and wail for your miseries that are coming to you… Listen! The wages of laborers who mowed your fields, which you kept back by fraud, cry out, and the cries of the harvesters have reached the Lord of hosts.” – James 5: 1 – 6

How is a fair wage determined?

Socialists and Reds have a bad reputation in the mouths of rich and powerful characters in the movie. They are “agitators” and “troublemakers.” Why are they so despised? Who is working to help the poor and downtrodden in the movie?

“Cursed be anyone who deprives the alien, the orphan, and the widow of justice. And all the people shall say, Amen!” - Deuteronomy 27: 19 What does the movie have to say about this verse?

The service station attendants say that the Joadas, and all the Okies like them, “…got no sense and no feeling; they aint human. A human being wouldn’t live like they do. A human being couldn’t stand to be so dirty and miserable. They aint a hell of a lot better than gorillas.” (Grapes, 301) What should our attitude be towards those who are less fortunate?

The book and the movie are both structured on the progression from the “I” to the “We”, from a struggle of the individual to the struggle of the group. What does the Christian faith have to say about the struggle of the community? How does that play against the American value on “rugged individualism”?

The following quote is often attributed to Karl Marx: “The rich will do anything for the poor, but get off their backs.” Is that an accurate statement?

“Then I looked again at the injustice that goes on this world. The oppressed were crying, and no one would help them. No one would help them because their oppressors had power on their side.” Ecclesiastes 4:1 As the woman who was accidentally shot in the “Hooverville” lies bleeding to death, one of the deputies rather callously says, “what a mess those .45s make” How is power and wealth used against the poor? Who makes the law? Who enforces it?

“I’ll be all around in the dark. I’ll be everywhere; wherever you can look,

wherever there’s a fight so hungry people can eat, I’ll be there. Wherever there’s a cop beatin’ up on a guy, I’ll

be there. I’ll be in the way guys yell

when they’re mad. I’ll be in the way

kids laugh when they’re hungry and they know supper’s ready. And when people are eatin’ the food they

raised and livin’ in the houses they built, I’ll be there too.” – Tom JoadWhat is more important – ownership and possession or work and labor?

How does Jim Casey, the former preacher, embody a “Christ figure”?

“They payin’ you 5¢?” “Come now, you rich people, weep and wail for your miseries that are coming to you… Listen! The wages of laborers who mowed your fields, which you kept back by fraud, cry out, and the cries of the harvesters have reached the Lord of hosts.” – James 5: 1 – 6

How is a fair wage determined?

Socialists and Reds have a bad reputation in the mouths of rich and powerful characters in the movie. They are “agitators” and “troublemakers.” Why are they so despised? Who is working to help the poor and downtrodden in the movie?

“Cursed be anyone who deprives the alien, the orphan, and the widow of justice. And all the people shall say, Amen!” - Deuteronomy 27: 19 What does the movie have to say about this verse?

The service station attendants say that the Joadas, and all the Okies like them, “…got no sense and no feeling; they aint human. A human being wouldn’t live like they do. A human being couldn’t stand to be so dirty and miserable. They aint a hell of a lot better than gorillas.” (Grapes, 301) What should our attitude be towards those who are less fortunate?

The book and the movie are both structured on the progression from the “I” to the “We”, from a struggle of the individual to the struggle of the group. What does the Christian faith have to say about the struggle of the community? How does that play against the American value on “rugged individualism”?

The following quote is often attributed to Karl Marx: “The rich will do anything for the poor, but get off their backs.” Is that an accurate statement?

“Then I looked again at the injustice that goes on this world. The oppressed were crying, and no one would help them. No one would help them because their oppressors had power on their side.” Ecclesiastes 4:1 As the woman who was accidentally shot in the “Hooverville” lies bleeding to death, one of the deputies rather callously says, “what a mess those .45s make” How is power and wealth used against the poor? Who makes the law? Who enforces it?

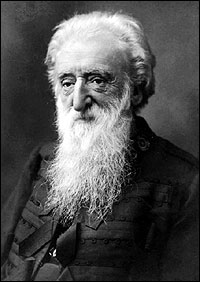

“While women weep, as

they do now, I’ll fight. While children

go hungry, as they do now, I’ll fight. While men go to prison, in and out, in and out, as they do now, I’ll fight. While there is a drunkard left, while there is a poor lost girl upon the street, while there remains one dark soul without the light of God, I’ll fight! I’ll fight to the very end!” - General William Booth of The Salvation Army

Sources

Ebert, Roger The Great Movies II, Broadway Books; New York, NY 2005.

Steinbeck, John The Grapes of Wrath, Penguin Books, New York, NY, 1939.

Steinbeck, John, ed Robert Demott, Working Days: The Journals of The Grapes of Wrath, Penguin Books, New York, NY, 1989.

Sources

Ebert, Roger The Great Movies II, Broadway Books; New York, NY 2005.

Steinbeck, John The Grapes of Wrath, Penguin Books, New York, NY, 1939.

Steinbeck, John, ed Robert Demott, Working Days: The Journals of The Grapes of Wrath, Penguin Books, New York, NY, 1989.

No comments:

Post a Comment